Batch 4 winner from USA

It's Up to You

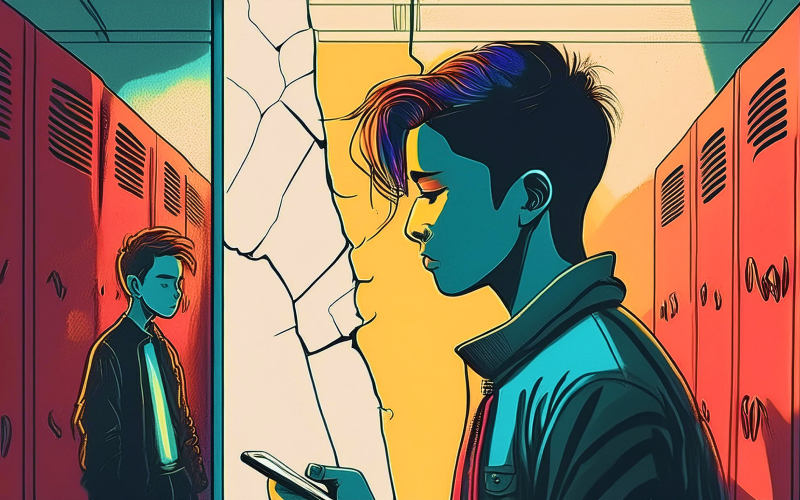

Bullying used to be something simple—as odd as that sounds. From the '80s til' the mid-2010s, kids' programming and sitcoms alike regularly depicted the stereotypical experience of the unlucky few students who found themselves at the bottom of their schools' social totem poles: being shoved into the shiny-red lockers during passing periods, walking past the gaggle of tank-top-wearing teenage girls laughing and pointing at another poor unfortunate soul, getting wedgied in the locker room, even eating lunch alone in the bathroom stalls (with a reproachful look or two at the camera for good measure). Pluck any student from the country out of their desk for a moment and ask them if they've experienced anything similar to this, however, and they would deny the notion (The Learning Network, 2024). Bullying has changed fundamentally, and society has failed to catch up to the beast that is adolescent cruelty many times over.

Part of society's consistent failure(s) in its response to bullying is just that—its response. "Zero tolerance" is a term that rose to popularity in the early 80s as schools began adopting harsh contraband restrictions as a consequence of the War on Drugs. Any infraction, no matter if it was the first of its kind by a student or so minor as to not even meet the government's standards for a drug crime, was punished the same. Soon after, school administrators began to expand the concept of a "zero-tolerance" policy to other matters on campus, bullying being the foremost target. In most schools, zero-tolerance policies for bullying meant that anyone seen in an "altercation," either physical or verbal, would be punished, often via suspension. At my own middle and high schools, for example, anything seen as remotely transgressive would result in a minimum one-day suspension for anyone involved. So, one might venture to think these policies were more than effective in curbing any bullying that could have been permeating the hallways—right? No. Frankly, it ended up being a convenient tool for school administrators to occasionally rope a few students who might have been in the wrong place at the wrong time into picking up some campus litter for a lunch period or two. The era of zero-tolerance was an objective failure for me and countless other students. All it provided students was a cover under which bullying could only escalate. It was akin to using a filthy cloth to bandage an injury; the wound would not be cured, merely hidden and left prone to infection—the "trench foot" of early 21st and late 20th-century education policies, so to speak. Under zero-tolerance policies, victims of bullying were forced into situations in which standing up for themselves or contacting a school administrator was dissuaded under the threat of punishment.

I mentioned having felt "failed" by zero tolerance during my years in middle and high school. I, like many other students across the globe, found myself at the bottom of both of my schools' respective social totem poles. I was a (seemingly) regular student at first glance, but apparently, my peers saw something more. The dreaded-by-adolescents "g-word" and I are quite well acquainted. I distinctly remember the first time I was called "gay," too. I was in fifth grade, about to serve the ball in a heated game of tetherball (that I was winning, by the way, not to brag or anything) during recess, and as I positioned the ball into place, I heard it.

"You're so gay."

My opponent, the stereotypical "large and in charge" popular student, grinned as he said this—like it was the funniest joke ever, even more so due to my evident confusion. I had never heard the word before, but apparently, I was one of the only people in that boat because the kids lined up at the then-freshly-painted white court line had made no real effort to hide their giggles. The perturbed feeling I had as a 10-year-old as I heard that word will always be ingrained into my memory. I would probably sooner forget my own name than that peculiar, skin-prickling feeling as I felt the social structure around me actively shift. I asked what it meant and received no response, just more giggles. Peeved at their behavior, I recall storming off to the classroom early that day. I eventually found out what the word meant nearly a year later after having first heard it when I was in sixth grade. By that point, I had heard it several more times and finally decided to google the word. To say I was disgusted would be an understatement. Seeing the word that had been used to describe me being defined as "sexually or romantically attracted to people of one's own sex" was a shock (Merriam-Webster, 2024). To my knowledge, I had never had such feelings. So why were they calling me this?

Was it my voice? My clothes? My hair? Something about my face, maybe? A birthmark that somehow gave it away?

I scoured everything about myself to try and figure out why, and frankly, I have failed to find an answer to this day. Perhaps it was merely always just that cruel sixth sense adolescent kids have where they manage to pick on something sensitive. Whatever it was, it kicked off a longstanding cycle of self-loathing and internalized homophobia. For reference, like most of my peers at the time, I was born to immigrant parents in the southern part of Cupertino, California. Cupertino is an interesting town. It is mostly immigrants and their children from Asia who brought their conservative values from their home countries. Just take a walk across the street from the suburban 2-3 million dollar homes that these immigrants live in, and you will be bound to run into some dilapidated apartment buildings or unhoused individuals, taking shelter as the midday sun beats on their sleeping bags. It is a city with a poignantly unique social and financial climate: conservative but overwhelmingly democratic, diverse but overwhelmingly Asian, and wealthy but also poor. These contradictions led to intense factionalism in the school systems there, where individual students were effectively reduced to a checking list of sorts.

Were you not Asian? Dark-skinned? Were you fat? Short? Hairy? Ugly? Wore glasses, maybe?

Were your parents poor?

Were they not doctors, lawyers, or engineers?

Did you live in an apartment instead of a house?

Did you wear Jordans? Or did you wear the generic brands?

Were you unathletic? Dumb? Not in an advanced math class?

Were you gay?

I could keep naming qualifiers for a solid hour or two. Kids are good at many things, and "othering," or treating people differently because they fail to fit in, is certainly one of them (Cherry, 2023). I unfortunately failed that last category. Something about me was just gay. Those kids sniffed it out like they were sharks, and I was the helpless woman swimming nearby, unaware of the cut on my ankle.

My five-person family and I lived in a tiny, somewhat dilapidated two-bedroom apartment on the edge of town. I was certainly not as well-off as my peers, and so I made strides to make myself like my classmates in any other way I could. I wore sunscreen if I had to go out and help my mom get groceries because if I got too dark from just being in the sun, I would be humiliated. I made sure to be good at P.E. so I would not be the kid straggling at the end of each mile run that everyone who finished "cheers on." And if those cheers resembled thinly veiled jeers at the thick legs of the girls who were still a lap behind everyone else, no one would be the wiser. Because at least that was not me. I made sure to walk home every day instead of having my mom drive up to the pickup spot because if my classmates saw me get in a battered 1998 Toyota Corolla amidst a sea of Teslas and BMWs, maybe they would look twice and notice my shoes and backpack had conspicuously been the same for a couple of years, or that no one had ever really ever seen me eating lunch. I worked hard to study and be in the most advanced classes because I knew what the kids next to me had said about the unfortunate few who were in Algebra I rather than Trigonometry in seventh grade.

Unfortunately, I got stuck with the one thing I could never really change. I was bullied relentlessly for seeming gay, no doubt in large part due to the conservative attitudes towards queerness that many of these immigrants had passed on to their children over. Asia, as a whole, tends to not be the most accepting place for pro-LGBTQ+ sentiments. For example, India only decriminalized homosexual behavior in 2018, and the Facebook post my parents learned about that news from was certainly met with much of their ire, let alone people who were far more traditional than them in our town (Kidangoor, 2018). Unfortunately, much of those attitudes passed onto me, and in combination with the constant bullying, caused me to internalize my homophobia in such a way that I distinctly recall the denial I was in when things finally "clicked" for me. It was seventh grade, and as I was walking home from school, I think something in my brain finally clicked that I had never really had the same feelings for girls that I was taught every one of my gender was meant to experience. Instead of just accepting it or even going the "simple route" of denying those feelings entirely, I actually blamed the bullying itself for making me gay. I am not really one for tears, but I do distinctly remember angry crying as I fast-walked home through the various fences and fields I had walked across for years at this point—but this time was different: something had changed in the way I would navigate the world forever. I was angry and confused, and I believed that I would have been straight had it not been for that one grinning person who spread a rumor that had surrounded me for nearly three years at that point and would continue to do so up until my later high school years.

The transition from middle to high school was probably the worst part of my high school experience. When I was in school, the anti-social justice warrior era of YouTube and entertainment in general was in full force. It was considered funny to say slurs and make "edgy" jokes at the expense of whatever minority group, as long as they were just that: a minority (Cass, 2011). And me and the f-slur certainly became well acquainted during my high school career. I could not go through a single lunch period without hearing those cursed six letters, even from people I would consider "friends." I was unable to stand up for myself or say anything back. What would it do? If I said anything of the same caliber back, you could bet on the fact that I would be sent home with a suspension as soon as I spoke. As a result, I started to withdraw from my extracurriculars, clubs, and even my academics. I would race to the library during lunch and sit in a quiet corner to read until the bell rang. Many students suffer similar socialization issues as a result of bullying. Of course, I was unable to avoid the worst of it. The bullying became significantly worse when teenage hormones came into play. One day, after school, I was sexually assaulted in the school's locker rooms by a student in my grade. I told no one, of course. How could I? If the gay student of the school goes and complains about being assaulted, there is no justice.

"Did you tempt them? Are you sure you weren't the one who initiated it?"

A single rebuttal from that student or his parents and I would have been finished. Sent packing with a signed expulsion notice, no questions asked. So I told no one, not even my parents. Zero tolerance failed me because it put me in so many situations in which I could do nothing. No one will admit to being an aggressor, ever. It was always two people getting punished or none at all. And while zero-tolerance policies have lately become a subject of ire from school administrators and the public alike and slowly walked back as a result, I still think it is important to realize that schools are failing to get kids the resources they need to cope with bullying because this is the cold, hard truth: bullying will always exist.

Bullying has evolved. It is now more underhanded and occurs primarily online. Bullying is not as simple as shoving kids into lockers anymore. Instead, it is as sneaky and humiliating as making group chats without one specific person or spreading nonconsensual images of people on social media, like Instagram stories that disappear in 24 hours (The Learning Network, 2024). Someone might not have concrete proof of being bullied nowadays, but they certainly do feel it—the "otherization" is the point, after all. For this reason, I have come to hold onto a personal belief that while a proper, safe environment is ideal, it may veer too far into being idealistic for some students. For those students, like me, it is up to them to overcome it. It does not have to be on their own, but they should not rely on mercies of the world in hoping that their bullies suddenly see the light and choose to stop their antagonistic behavior. I changed schools when my family moved right before the COVID-19 pandemic. And while that stopped the bullying, you do not overcome something as psyche-affecting as bullying simply because it is in your past. I joined therapy and GSA programs to try and reach out to a community that had experienced many of the same struggles I did and was more than willing to share its love, care, and acceptance with a fledgling like me. In therapy, I learned about being more accepting of what happened and moving on from it without necessarily needing to forgive those involved (Gregory, 2022). I am happier now, and it is because I found community—something that schools have, in my opinion, failed to provide for their marginalized students.

In my community, I advocated for the local GSA online and was the lead graphic designer for a nonprofit called Bigger Puzzle that used to spread awareness and useful information about neurodivergent individuals, who are a group of people who are also incredibly marginalized and bullied in schools. Stopping bullying, in my opinion, is a futile endeavor. But stopping bullying from affecting people so heavily by providing communities for them to socialize and make friends with others like them is certainly worthwhile because people like me all over the world are too often robbed of that opportunity. Perhaps if we could prevent people from being harmed by bullying, bullying might begin to slowly fade rather than evolve as it always has when one form of bullying is no longer viable due to whatever policy or monitoring system is trending. Bullying exists to make people feel "less than," and if they no longer feel that way, bullying no longer has a reason to exist.

I was introduced to Bigger Puzzle through the GSA, and using my designs, we would regularly put out posts correcting common misinformation about neurodivergent people. It was a way to get involved in something that did not hit too close to home to be triggering. It was some of the most fun and meaningful volunteer work I have done, and it inspired me to think about similar ways more schools could offer community to students who lack it. Discord was a haven for my high-school self and even my college self. It allowed me and others like me to make friends online and not feel like we were fundamentally flawed or outcasts. Perhaps schools should advertise online communities like Discord channels for certain communities rather than just the local clubs on offer. Technology and the internet as a whole were the "great flatteners" of the world. Businesses could suddenly become global and employ anyone, not just people near their headquarters (Friedman, 2005). In the same vein, online communities have begun to flourish and offer victims of bullying a chance to feel like they are a part of something. The adolescent socialization of bullying victims should not be left as a carcass for bullies to devour as they see fit. Students who lack community should be extended it in other forms, mainly online. Schools have an ethical responsibility to provide resources for the access of those communities to their students in the form of links, guides, and the equipment and internet necessary to access such things, lest they fail another generation as they did mine. I lived through six grueling years of constant bullying and would be remiss if I did not use my ability to reflect on that time to help others who may be in the same position as I was.

Works Cited

Cass, C. (2011). Poll: Young people see online slurs as just joking. NBC News.

https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna44591677.

Cherry, K. (2023). How Othering Contributes to Discrimination and Prejudice. VeryWell.

https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-othering-5084425.

Friedman, T. (2005). It's a Flat World After All. The New York Times.

https://www.nytimes.com/2005/04/03/magazine/its-a-flat-world-after-all.html.

Gregory, A. (2022). Why Forgiveness Isn’t Required in Trauma Recovery. Psychology Today.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/simplifying-complex-trauma/202202/why-forgiveness-isn-t-required-in-trauma-recovery.

Kidangoor, A. (2018). India's Supreme Court Decriminalizes Homosexuality in a Historic Ruling for the LGBTQ Community. TIME.

https://time.com/5388231/india-decriminalizes-homosexuality-section-377/.

Merriam-Webster. (2024). Gay. Merriam-Webster Incorporated.

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/gay.

Roberge, G. (2012). From Zero Tolerance to Early Intervention: The Evolution of School Anti-bullying Policy.

Laurentian University. https://in.nau.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/135/2018/08/From-Zero-Tolerance-to-Early-Intervention-ek.pdf.

Stahl, S. (2016). The Evolution of Zero Tolerance Policies. CrissCross.

https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1026&context=crisscross.

The Learning Network. (2024). What Students Are Saying About Bullying Today. The New York Times.

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/03/21/learning/what-students-are-saying-about-bullying-today.html.